It seems so long ago that the destruction of Falluja was hailed as the turning point that would lead to peace in Iraq.

Of course that was about three turning points ago.

But it is important that we on the anti-war left remember what was done to the city, and now, at last an independent journalist has managed to gain entry into the cirt and report what it is like now.

"We Regard Falluja As a Large Prison"

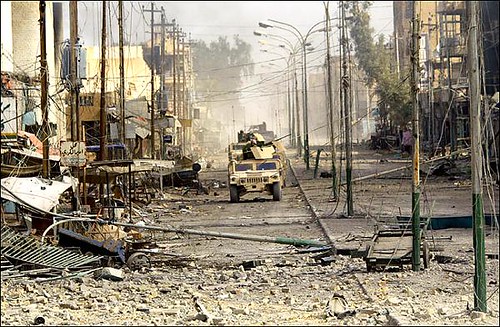

Eight months after the second invasion of Falluja, there is hardly a street that does not still feature a building pulverized during the assault. I had not been in the city since last July, when I was escorted out by three cars of mujahedeen — that's when things were still relatively nice — and though I had expected it, the destruction was still shocking.

The dome of one mosque I had previously used as a landmark was completely missing, large holes had been blown in others. Houses have been pancaked, it is hard to find a façade without the mark of at least small arms fire. As many as 80 percent of the city's 300,000-plus residents have returned, but the city has by no means returned to normal. On Sunday, the police were hard at work adding razor wire and new concrete blast barriers to the already sprawling fortifications around their main station in the center of town while US and Iraqi army patrols traversed the main street, the Iraqis firing their rifles in the air to clear traffic. Small arms chattered in the distance, followed by a response from a larger gun. The tension is palpable. Curfew begins at 10 p.m. but low-level fighting continues.

"They are killing one or two of us everyday," says an Iraqi soldier at one of the checkpoints into the city, a claim confirmed by local doctors.

.......

Back at the hospital, Ahmed says he expects the fighting to continue. "Even civilian people will change to be fighters," he says. "We regard Falluja as a large prison." (People in Falluja will not talk directly about fighting, though all indications are that the new attacks are homegrown.)

The Iraqi army in Falluja, who don't mind telling a journalist that they are all from cities in the south, don't seem particularly thrilled to be here. (When the USA tried recruiting Fallujis to fight in Falluja, they turned their guns on the US or turned them over to the guerillas.)

"Falluja — death," says one of them, drawing a finger across his throat, a motion that I would like to go one day in Iraq without seeing someone make.

.......

I approach some of the Marines on a base inside the city, to try and find out what life is like for them. They say there is no one at the base who can speak on the record, but I pause for a minute and chat, not terribly excited about walking back outside into the thick dust and, potentially, a line of fire. They ask why I have come, I am the first journalist they have seen in four months.

"No one wants to talk about Falluja," says one of the Marines.

The next time you hear or read one of pro-war chums witter on about libertating Iraq, remind them of Falluja, remind them of what continues to be done in their name.